BMW’s S 1000 RR, a decade later

The S 1000 RR is a dramatically different object de machina to its different stakeholders. To BMW, it is a loss leader to burnish and sportify its brand; to the BMW touring traditionalist, it is heretical; and to high performance enthusiasts, it singlehandedly dragged sport bike R&D out of the torpor of the global financial crisis and forced all major brands to respond with halo bikes of their own. In 2008, the competitors did not see that coming.

BMW has traditionally been able to charge a substantial brand premium for their bikes, partially by engineering to avoid direct product comparisons. The S 1000 RR turned that on its head, and despite clearly being more expensive to engineer and produce than most of the rest of the BMW product line, they priced it to compete head to head with the Japanese brands. Although that strategy was partially assisted through an expensive Yen and a cheap Euro, the combination of performance and price quickly led the S 1000 RR to a host of conquest sales, an increase in interest in the brand, and 14 percent of BMW U.S. motorcycle sales. Halo bikes are supposed to attract attention and convey a warm glow to less expensive offerings; ironically, BMW didn’t have anything in their product line that was less of a value.

The S 1000 RR is not a street bike. That is not to say you can’t ride it on the street—of course you can—but it is not engineered for street riding in any way, shape or form. Back before 1996, manufacturers engineered sport bikes in recognition that most of the bikes would never turn a wheel on a track. That ended abruptly with the ’96 GSX-R750, and the battle lines of race-ready supersport replicas were drawn. A manufacturer daring to rubber-mount their clip-ons, install rubber on the rear sets, or soften the power delivery or spring rates had their sport bikes derided at track-focused press launches by racer journalists. I know, as I was one of them. Mea Culpa.

The S 1000 RR is not a street bike. That is not to say you can’t ride it on the street—of course you can—but it is not engineered for street riding in any way, shape or form. Back before 1996, manufacturers engineered sport bikes in recognition that most of the bikes would never turn a wheel on a track. That ended abruptly with the ’96 GSX-R750, and the battle lines of race-ready supersport replicas were drawn. A manufacturer daring to rubber-mount their clip-ons, install rubber on the rear sets, or soften the power delivery or spring rates had their sport bikes derided at track-focused press launches by racer journalists. I know, as I was one of them. Mea Culpa.

Fortunately, motorcycle enthusiast culture adapted to the new machinery, and although racing participation had cratered in the U.S., track day riding culture has flourished with more race tracks, more tires and more opportunities for track riding than ever before.

Track riding is, simply put, nothing like riding on the street. Track riding is downhill ski racing compared to a walk around the block. Track riding is a freshly honed straight razor to the kindergarten safety scissors of street riding. It is dangerous, it is loud, and it is in a single pursuit of faster lap times. The difficulty of faster lap times increases exponentially so things quickly get out of hand with wear rates of, uh, everything. It embraces any technical solution which decreases the manifestation of human limitation. I ride on the street. I might even occasionally ride in a fashion which would be termed “spirited” by some or “criminal” by others. I have never entered a turn on the street, knee down indiscretions included, loading the front tire in a fashion in which I load the front on even a typical out lap on a track.

I say this in an attempt to convey that the S 1000 RR is a terrible street bike in the same way an F-16 is a terrible commuter plane. Of course it is, but that is hardly the point. Where I wouldn’t want to ride an S 1000 RR across D.C., I was happy to use them as a platform for seven years and three national titles of endurance road racing. Sadly, whereas the 2015 revision of the S 1000 RR did not obsolete our 2012 race bikes, the 2020 fully deprecates the earlier machines.

I say this in an attempt to convey that the S 1000 RR is a terrible street bike in the same way an F-16 is a terrible commuter plane. Of course it is, but that is hardly the point. Where I wouldn’t want to ride an S 1000 RR across D.C., I was happy to use them as a platform for seven years and three national titles of endurance road racing. Sadly, whereas the 2015 revision of the S 1000 RR did not obsolete our 2012 race bikes, the 2020 fully deprecates the earlier machines.

The key to getting around a race track fast is, literally, where the rubber meets the road. Whichever rider can best manage the contact patches of the tires wins. Those contact patches, however, are dynamic. Dry track tires are filled with carbon black and either have zero tread (slicks) or 4.1 percent negative space (DOT limit is 4 percent). These compounds are hydrophobic and won’t work on wet pavement, standing water, or if the tire is outside of its operating temperature range by being either too cold or too hot. We typically have tire compounds which are matched to the temperature of the track as well as the length of the riding event (i.e., a four-lap sprint or all-day track day). We set tire pressures to manage the running temperature of the tires but also to manage that contact patch. Every racer long ago adopted the use of tire warmers to electrically heat the tires to proper operating temperature before even rolling out of the pits. Track day riders make do with slightly less focused tires which are warmed up the old-fashioned way: by riding them.

Imagine looking at a glass plate from under the bike with a front tire sitting on the glass. Then double the weight on the front tire. The contact patch will spread out with the added load. The more we load a tire, the bigger the contact patch, and the more grip we can use. We can load a front tire by trailing the brake into the turn (transferring weight from the rear to the front) and, at a certain point, simply the act of turning loads the front. We then shift that weight to the rear wheel with the throttle to get grip on the rear tire to get us down the next straight. As power has increased over the last three decades, so has the need for wider and wider rear tires, but those wide rear tires make the bikes handle poorly, so then they’ve had to engineer handling around that.

Imagine looking at a glass plate from under the bike with a front tire sitting on the glass. Then double the weight on the front tire. The contact patch will spread out with the added load. The more we load a tire, the bigger the contact patch, and the more grip we can use. We can load a front tire by trailing the brake into the turn (transferring weight from the rear to the front) and, at a certain point, simply the act of turning loads the front. We then shift that weight to the rear wheel with the throttle to get grip on the rear tire to get us down the next straight. As power has increased over the last three decades, so has the need for wider and wider rear tires, but those wide rear tires make the bikes handle poorly, so then they’ve had to engineer handling around that.

They handle worse if you are at, say, 55 degrees of lean and cross a bump. The force of that bump is not absorbed by the suspension (which is at an angle now) but, rather, goes straight into the chassis. So we need a swing arm and frame which can support the forces of 200 HP at 190 mph, but also can deflect to absorb small bumps at full lean. Forks have to be stiff enough to not deform under the crushing loads of braking while still transmitting tire vibration to the rider so the riders can try to infer how much more grip is available for additional turning or braking.

Once the rider has begun to open the throttle, each piston pulse sends a shock of power down the chain to the tire. In a track environment, each power pulse actually causes the tire to break traction. If you start spinning a tire more than about 3 percent, the back of the bike will start to slide. If you don’t manage that slide, it turns into a high side when the tire hooks up again and throws the rider and the bike to the moon.

Once the rider has begun to open the throttle, each piston pulse sends a shock of power down the chain to the tire. In a track environment, each power pulse actually causes the tire to break traction. If you start spinning a tire more than about 3 percent, the back of the bike will start to slide. If you don’t manage that slide, it turns into a high side when the tire hooks up again and throws the rider and the bike to the moon.

For years, manufacturers played with asymmetrical firing orders (the best road race bikes all sport v-4 engines with asymmetrical firing orders) and other tricks to allow the tire more time to recover between pulses. We also play with swing arm angles, spring rates, and chassis geometry, and all of that generates mechanical traction. The more mechanical traction you have, the faster you can go.

Traction control takes away power the mechanical solution can’t handle. Traction control, on a road race bike, is not really to increase safety. Traction control, in a track context, is aimed to encourage the rider to get the throttle open sooner and wider by reducing the chance of a disastrous outcome. It is not there for “safety,” it’s there to help the rider get to WFO ASAP. Remember, at the track we’re pushing hard enough that sticky race tires on dry warm pavement are right at the limits of their adhesion, like driving a car on snow. You don’t want any inputs to upset that tenuous traction relationship.

BMW has employed a vast array of technological tricks on the S 1000 RR to make all of this more approachable for intermediate rider, not just racers.

Any high-performance, high-revving four-stroke engine has three phases of resonance. These are times when the intake tract and exhaust tracts are of just the right lengths to use reflecting sound waves to supercharge the fuel/air charge in the combustion chamber. This usually leads to brontosaurus-looking dyno charts where the power climbs rapidly when the RPM matches the engineered phasing, and dreaded flat spots when it isn’t. Carburetors made all this worse because you actually get air flowing backwards through the carbs before being sucked back through again, leading to the dreaded “triple enriched carburetion.” There are lots of tricks to mitigating this, but they all require compromises like using asymmetrical header pipe lengths, asymmetrical intake lengths, variable intake lengths, etc. All of those solutions work but sacrifice either some peak or mid-range power. The best solution would be to have two intake cams, one with low lift, low duration lobes, and another cam with high lift, long duration lobes. But, of course, that is impossible.

Any high-performance, high-revving four-stroke engine has three phases of resonance. These are times when the intake tract and exhaust tracts are of just the right lengths to use reflecting sound waves to supercharge the fuel/air charge in the combustion chamber. This usually leads to brontosaurus-looking dyno charts where the power climbs rapidly when the RPM matches the engineered phasing, and dreaded flat spots when it isn’t. Carburetors made all this worse because you actually get air flowing backwards through the carbs before being sucked back through again, leading to the dreaded “triple enriched carburetion.” There are lots of tricks to mitigating this, but they all require compromises like using asymmetrical header pipe lengths, asymmetrical intake lengths, variable intake lengths, etc. All of those solutions work but sacrifice either some peak or mid-range power. The best solution would be to have two intake cams, one with low lift, low duration lobes, and another cam with high lift, long duration lobes. But, of course, that is impossible.

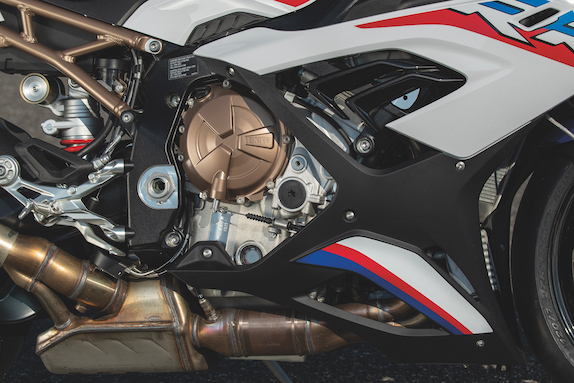

Except BMW did it. With ShiftCam technology, the 2020 S 1000 RR has two sets of intake cam lobes, one set with low lift and duration for low and mid-range power, another set with high lift and high duration for top end power. The ECU switches from one cam to the other at 9,000 rpm. Although the 2020 model only has six more peak power than its predecessor, the midrange boost is huge. Of course, the unkind might point out you’ll rarely get to use mid-range power because usually the traction control or wheelie control will be limiting the torque to whatever the tire can handle, but once in while you will get to use it, and it is welcome.

BMW is selling the S 1000 RR in a variety of trims with price points ranging from the base $16,995 up to the M model at $22,095. Basically, you get more track-focused parts as you spend more on the purchase price, and honestly, the M package is a deal, as it comes with full carbon wheels which, in the aftermarket, cost $3,500 by themselves. So, with the M model you get the carbon wheels, Li (lighter) battery, a less locked ECU (allowing access to more modes, but not full access). The M model is a whopping 32 pounds lighter than the 2019 bike. That kind of weight reduction, all while having to conform to tighter emissions standards, is breathtaking from a racer standpoint.

BMW is selling the S 1000 RR in a variety of trims with price points ranging from the base $16,995 up to the M model at $22,095. Basically, you get more track-focused parts as you spend more on the purchase price, and honestly, the M package is a deal, as it comes with full carbon wheels which, in the aftermarket, cost $3,500 by themselves. So, with the M model you get the carbon wheels, Li (lighter) battery, a less locked ECU (allowing access to more modes, but not full access). The M model is a whopping 32 pounds lighter than the 2019 bike. That kind of weight reduction, all while having to conform to tighter emissions standards, is breathtaking from a racer standpoint.

A BMW representative at the event was clear the bike is aimed at track day riders and poseurs-or “aspirational brand enthusiasts” as he described them. I am not sure how “aspirational brand enthusiasts” weigh their consumption decisions, but light rims (ala these carbon ones) tend to transform the handling of liter bikes for the better. One of the many enemies of nimble handling are the gyroscopes inherent in the system. The three big ones are the front wheel, the rear wheel, and the crank shaft. A gyroscope responds to inputs with a reactionary torque at 90 degrees to the input. So, not only are those gyroscopes resisting the turns, they are actually trying to twist the frame (or cases) in the opposite direction, minus 90 degrees. Lighter crank shafts make a noticeable improvement in handling, particularly when that sucker is spooled up to 14,600 rpm with a late downshift into a 120 mph turn, but that lighter crank also spins up faster with throttle inputs, which decreases mechanical rear traction. Most MotoGP bikes, and a couple sporting street bikes, currently spin their longitudinally arranged crankshafts backwards so the gyroscope of the crank is offset, to some degree, by the wheels spinning forwards.

Lighter wheels, barring catastrophic failure, have no “buts.” Lighter wheels brake faster, accelerate quicker and turn much faster. The difference between even cast aluminum wheels and the lighter forged aluminum wheels, in this rider’s experience, tightens apexes by three feet. Going from cast aluminum to forged magnesium or, in this case, carbon fiber, is like switching from ski boots to dancing shoes. There is also some benefit from the reduction in unsprung weight to allow faster suspension response to bumps, but honestly, most of the places on a track where you really want that, the suspension isn’t really doing a whole hell of a lot because you are cranked over in a turn.

Lighter wheels, barring catastrophic failure, have no “buts.” Lighter wheels brake faster, accelerate quicker and turn much faster. The difference between even cast aluminum wheels and the lighter forged aluminum wheels, in this rider’s experience, tightens apexes by three feet. Going from cast aluminum to forged magnesium or, in this case, carbon fiber, is like switching from ski boots to dancing shoes. There is also some benefit from the reduction in unsprung weight to allow faster suspension response to bumps, but honestly, most of the places on a track where you really want that, the suspension isn’t really doing a whole hell of a lot because you are cranked over in a turn.

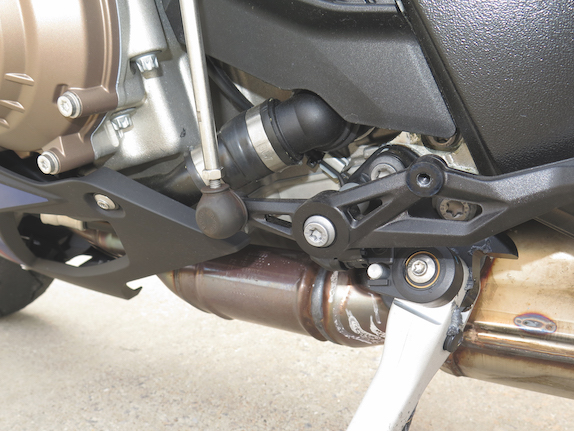

This is why BMW softened the chassis for 2020. The 2009 bike was clearly built for billiard-ball-table-smooth European tracks and slicks with massive grip. It also might have been designed by engineers who had “stiff is good” on the brain. The forks were massive, the frame was massive, and the swing arm was massive. The bike could brake like crazy because there was no flex anywhere in the system; however, once on its side on American rough tracks, it tended to buck and pump. BMW has finally addressed this with the Motorrad Flexframe with allows the bike to flex a bit sideways at full lean. The softer the chassis, the more feedback to the rider as well, until the bike is too soft and then it wobbles, shimmies, and shakes, and then we complain about that instead.

Barber Motorsports Park and museum are what happens when you have a motorsports enthusiast with no budgetary constraints. George Barber’s museum is spectacular and has something like 1,400 bikes in it, all in perfect running order. He built a track to test the restorations, and the track, although missing a high speed straight, is a thing of beauty in its topography, architecture, landscaping and art. The complex is just north of Birmingham, Alabama, and hosts the country’s largest motorcycle event with the Barber Vintage Festival. We had it all to ourselves with a fleet of 2020 S 1000 RRs.

Barber Motorsports Park and museum are what happens when you have a motorsports enthusiast with no budgetary constraints. George Barber’s museum is spectacular and has something like 1,400 bikes in it, all in perfect running order. He built a track to test the restorations, and the track, although missing a high speed straight, is a thing of beauty in its topography, architecture, landscaping and art. The complex is just north of Birmingham, Alabama, and hosts the country’s largest motorcycle event with the Barber Vintage Festival. We had it all to ourselves with a fleet of 2020 S 1000 RRs.

I did my best to elude the various electronic and riding nannies, and, although I escaped the human control riders, my first stint on the bike was in “Road” mode. We were riding on Pirelli DOT race tires with an SC1(soft) front and an SC2 (medium) rear but without warmers. The tires predictably squirmed around a bit until they came up to temperature. However, even once the tires were warm, the bike felt squishy. The suspension was transferring too much front and rear due to the ECU setting the front and rear damping at “too squishy for track,” and stranger still, the bike’s power was really abrupt. The Inertial Monitoring Unit (IMU) was telling the ECU the bike was leaned over, so the ECU wouldn’t let the butterflies open and instead just blinked the TC light on the dash at me. I kept finding myself at full throttle in second gear and decked at the apex with nothing happening. Then, as I weighted the outside peg and picked the bike up, the ECU would feed in the rest of the power and the bike would take off. It all felt awkward and unnatural. I guess there is an argument about those being “street” settings, but I can’t imagine wanting to even canyon carve on those settings.

Just before I rolled out for our second track session, one of the more sympathetic technicians leaned over and set my bike to “Race” mode. These settings (faster power, less TC, less wheelie control, less ABS, less engine braking) started to actually feel like a liter bike. However, it wasn’t until it was set in Pro Mode 2 it really came alive. Longtime BMW racer and BMW Brand Ambassador Nate Kern suggested I set the traction control to -3 (from a range of +7 to -7) and then the bike showed its real potential.

Just before I rolled out for our second track session, one of the more sympathetic technicians leaned over and set my bike to “Race” mode. These settings (faster power, less TC, less wheelie control, less ABS, less engine braking) started to actually feel like a liter bike. However, it wasn’t until it was set in Pro Mode 2 it really came alive. Longtime BMW racer and BMW Brand Ambassador Nate Kern suggested I set the traction control to -3 (from a range of +7 to -7) and then the bike showed its real potential.

With the electronic choke collar removed from the throttle bodies, brakes, and coils, the S 1000 RR became an extremely competent track weapon. You want some wheel spin on the back under throttle and at -3 my bike would just start to leave black lines from the tire, but without starting to pump, and far from any threat of a highside. The front tire had tremendous grip (all track tires do) so the lack of any ABS was inconsequential. The Barber track has many cresting blind turns. These crests are often when the bike is heavily loaded on the rear wheel, which encourages the front wheel to lose contact with the tarmac to either exhilarating, or excruciating, effect. Older S 1000 RR wheelie control caused the bike to porpoise but the new IMU enhanced system allows the bike to carry a small wheelie without upsetting the chassis. In Pro Mode 2 the bike felt like an incredibly powerful, fast, predictable track bike.

Suspension persists as the black art of motorcycles. Many, many bikes I see (street or track) are set up wildly off from ideal; everything from tire pressures to spring and damping settings, and we’re not even going to start to talk about geometry. BMW, in their best nanny engineering, knows most riders won’t check tire pressure, much less dial in suspension settings, so they have made some educated guesses about what would be most appropriate. Now, if you have Ohlins suspension, an Ohlins suspension tech, an array of springs and valving, and a service truck, you would, perhaps, be able to arrive at better suspension settings for a race track. However, for off the shelf components, the BMW set up works well in being able to just hit a few buttons and change from fast and soggy (i.e., comfortable) to slow and tight (i.e., racey).

Suspension persists as the black art of motorcycles. Many, many bikes I see (street or track) are set up wildly off from ideal; everything from tire pressures to spring and damping settings, and we’re not even going to start to talk about geometry. BMW, in their best nanny engineering, knows most riders won’t check tire pressure, much less dial in suspension settings, so they have made some educated guesses about what would be most appropriate. Now, if you have Ohlins suspension, an Ohlins suspension tech, an array of springs and valving, and a service truck, you would, perhaps, be able to arrive at better suspension settings for a race track. However, for off the shelf components, the BMW set up works well in being able to just hit a few buttons and change from fast and soggy (i.e., comfortable) to slow and tight (i.e., racey).

I weigh in at 170 pounds and the bike worked really well. My sparring partner for the day was the love of my life and race teammate Melissa Berkoff. She weighs 110 pounds. Usually we need to respring bikes for her weight before the bike will respond at all. She reported the bike was oversprung for her (of course), but it handled well. Although track riders should be checking tire pressures at multiple times during the day, many riders don’t. Or they forget. Or they get their new tires back from the tire truck and forget to reset the pressures from mounting pressures to riding pressures. BMW has installed a tire pressure monitoring system on the bike I was testing (it’s one of the upgrade options). My guess is, of all the electronics on the bike, this is the one system that will provide the most handling improvement to street riders.

The 2020 S 1000 RR keeps BMW current against the best of liter class sport bikes from Japan and Italy. It is an incredibly sophisticated track weapon that can be approachably tuned by intermediate or expert riders and quickly put to devastating effect on a race track. BMW has done an incredible job of putting electronic leashes on a fire breathing dragon to make it more domesticated, but never forget life comes at you fast with 200 hp.

The 2020 S 1000 RR keeps BMW current against the best of liter class sport bikes from Japan and Italy. It is an incredibly sophisticated track weapon that can be approachably tuned by intermediate or expert riders and quickly put to devastating effect on a race track. BMW has done an incredible job of putting electronic leashes on a fire breathing dragon to make it more domesticated, but never forget life comes at you fast with 200 hp.

Riding and wrenching motorcycles since 1983, Sam Fleming has clocked over 100k each on a Slash 5, an R 90 S and a K 100 RS while ticking off the 49 states before he was 20 years old. His endurance road racing team ARMY OF DARKNESS has won 10 national championships since 1996, including BMW’s first, second and third U.S. national endurance championships on S 1000 RRs. He is based in Washington, D.C.