Just my imagination

No, not the 1970s super-hit—I’m talking about my actual imagination running away with me!

I’m a creative guy. That’s not a boast, as it can be every bit as much a liability as an asset. A mind churning out endless possibilities can solve problems in ways others might not consider and allow foresight others might not possess. It can also generate tons of nonsense that ends up distracting, confusing, and frightening me needlessly.

I’ve always wanted the job of “Idea Man,” that mythical position in old black-and-white movies. Apparently, big city businesses used to pay such employees huge sums of money just to come up with new ideas, no follow-through required. Maybe there was an imagination shortage back in the day, but if someone were foolish enough to pay me by the idea, I’d be obscenely rich, even if it were only “a penny (each) for my thoughts.”

Listen to this column as Episode 22 of The Ride Inside with Mark Barnes. Submit your questions to Mark for the podcast by emailing [email protected].

As usual, the idea for this column came to me on a ride. I was cruising down a multi-lane highway and found myself behind a flatbed truck carrying an assortment of machines, scrap metal, and furniture. A few things were sloppily tied down with rope, but the driver trusted gravity to hold most of it on the unfenced platform. As soon as I got a good look at this disaster waiting to happen, I immediately changed lanes, then passed to get completely out of harm’s way—but not before this intermediate step: I automatically visualized various items from that payload sliding off the back of the bed and tumbling toward me at lethal speed. In a split-second my mind’s eye beheld numerous scenarios, with various objects breaking free, individually and in combination. These were vivid, elaborately detailed visions, including the grand finale of a chair hurtling at eye level, one of its legs ultimately stabbing through my visor. Alarming imagery, for sure; it provided plenty of motivation to take proactively evasive action.

As dramatic as these flashes were, they didn’t arouse the terror that would accompany any such events in real life. I registered the danger as though noticing a crosswalk warning. There was a moment of heightened alertness, several reflexive changes in speed and direction, and the whole thing was over. The only lingering remnants were brief disdain for the carelessness of the truck’s occupants and a mental note about how vigorously my imagination had exercised itself in such a fleeting timeframe. I was reminded of times I’ve awakened, looked at the clock, fallen back asleep, and dreamt some epic saga, only to awaken again and discover only a few minutes had passed; the dream had seemed to last for hours. Mental time and clock time are not the same.

In this example, my imagination—while arguably overwrought—served a valuable function. It alerted me to consequential possibilities and did so faster than the speed of normal thought. I did not survey the scene in front of me, wonder about what might happen, consider the odds, plan out a strategy, and then execute a logically reasoned course of action. Instead, everything was efficiently contained in an image; it’s true, “a picture is worth a thousand words.” I reacted to the image (in this case, an unnecessarily redundant series of images) without thinking, as it was all so utterly obvious no conscious processing was required. When navigating my living room, I don’t stop and think about how to walk around the couch, I simply do it. So it was with the flatbed truck.

Something similar happens when I see a stack of objects precariously balanced on a shelf. My imagination automatically streams a video clip of those things toppling to the floor in response to the slightest provocation, and I reorganize them into a more stable arrangement. When working in my garage, I’m often peppered with images of what could go wrong. The Murphy’s Law app in my brain is forever running in the background and broadcasting notifications. An untethered wire could snag on something and get yanked loose; a crumb of debris teetering above an open orifice might fall inside and wreak havoc; a tool on the floor would surely roll underneath my foot if I were to absent-mindedly step on it, leading to a fall. While riding, my mind conjures countless images of what might await around blind corners, including both realistic and unrealistic possibilities…

Therein lies the rub. While it can be invaluable to foresee problems before they happen, the imaginative process doesn’t necessarily factor in probabilities. It’s too busy coming up with ideas to evaluate each one’s merit. Hence, anticipatory visions of loose gravel or an oncoming vehicle straddling the centerline—things commonly encountered on one of my favorite twisty roads—can prompt prudent choices of corner entry speed and lane position, but it would be absurd to brace for impact with a bear around every bend. Though I really did once come around a mountain switchback to find a bear crossing the road, this was (so far, at least) a once-in-a-lifetime anomaly. Needless to say, the surprise encounter left an impression, despite the extremely lucky lack of physical impact, and it’s frequently reprised by my imagination, despite its minuscule chance of happening again. This particular image is easily dismissed, but a host of others can torment me, detracting from my riding pleasure and performance, rather than enhancing them.

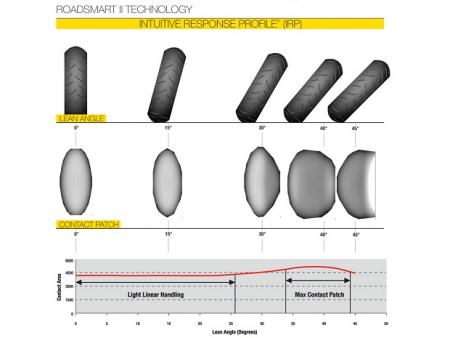

A variety of traction-erasing surface contaminants are the most plentiful hobgoblins. It’s good to be vigilant for oil on the road where I might plant a foot when stopping at a light. It’s also wise to be wary of dark patches in the road ahead, knowing they could be slick fluid or slippery tar. Of course, they might also be completely harmless shadows, but better safe than sorry, right? Maybe. On one hand, avoiding predictable peril should be top priority—“safety first!” On the other hand, this can be taken to such an extreme it begs the question why I’d ride a motorcycle in the first place, regardless of all the risk-mitigation measures I might take (ATGATT, rider training, etc.), and it could reduce my safety by spooking me into erratic maneuvers.

Every time I approach an intersection, I imagine surrounding traffic making catastrophically bad moves. I could end up refusing to enter the fray on the basis of such fantasies, but then I’d have to worry about being hit from behind. Likewise, dodging every dark spot in the road would result in a weaving path doubtless more likely to end in a crash than rolling though a puddle of almost anything. In the case of the intersection, my calamitous visions compel me to cover my controls, scan for escape routes, and basically ride as though I’m invisible to nearby drivers. When suddenly confronted with a splotch of black on the street, I shift into “ultra-smooth mode” and avoid braking, turning, or accelerating while traversing the unknown substance instead of swerving around it.

What I just described is healthy enough, but here’s the rest of the story. I can conjure a multitude of additional images in rapid-fire succession while approaching any corner, blind or not. I easily imagine an invisible film of silt that could cause an instantaneous low-side crash. I’ve seen it happen, though only once. I can also recall watching a riding buddy go down because he hit a patch of diesel fuel that blended in perfectly with the shade from an overhanging tree. He wasn’t heeled over, dragging a knee, but just happened to somehow arrive at exactly the wrong angle. I witnessed this in my mirror, having rounded the same bend in an arc only inches different than his, never even noticing the fuel as I passed it—I may have even ridden right over it! Replaying a scenario like this isn’t as absurd as fearing Godzilla might pop out from behind a roadside bush, but it would be ridiculously impractical to enter every corner expecting my tires to slide out from under me. Whether my imagination works from memory or forecasts new threats based on extrapolation, an overabundance of scary images can be a real problem, one that could easily cause more trouble than any of the “foreseen” hazards. Excessive worries are distractions from the mental tasks essential to safe riding, they create physical tension that interferes with good technique, and they certainly preclude the fun riding is supposedly all about.

I’ve often felt envious of the blissful ignorance of some new riders. They don’t know enough yet to recognize the actual dangers they may narrowly evade. My heart might stop while watching one unwittingly do something terribly dangerous, while they remain completely unflustered. Obviously, there’s a serious downside to such naïveté, but I would love to ride free of the potentially crippling awareness of all the bad things I’ve seen, read about, heard others describe, and know are out there somewhere, waiting to ruin my day, my bike, and my body. Fortunately, I can usually ignore my wilder notions and rein in my idea generator with some rational thought that does consider probabilities.

However, the most effective remedy involves repeatedly refocusing on the routine tasks and sensations of riding. As in meditation, it’s virtually impossible to empty the mind of unwanted thoughts, but it’s not too hard to displace them with an alternative target of attention. That may mean resuming focus on the breath or a candle flame—perhaps a hundred times during a meditation session. On a motorcycle, it means occupying our minds with smooth control inputs, thoughtful line selections, proper posture, and strategically distributed muscle tension/relaxation. When imagination becomes a liability instead of an asset, we must replace the abstract with the concrete. Not coincidentally, this is also the way to invite a state of flow, as opposed to the fragmented or paralyzed state of overthinking.

Mark Barnes is a clinical psychologist and motojournalist. To read more of his writings, check out his book Why We Ride: A Psychologist Explains the Motorcyclist’s Mind and the Love Affair Between Rider, Bike and Road, currently available in paperback through Amazon and other retailers.