Understanding octane – AKI, MON and RON, oh my!

I’m as excited about the new F 750 and 850 bikes as just about anybody who loves to look at new motorcycles but isn’t going to buy one of those because they’ve got their eye on a different bike already, and by “eye on,” I mean “deposit paid.” Paul Guillien, MOA member, dedicated off-road rider and oh by the way, CEO of Touratech USA, did a great job whetting my appetite for the next generation of BMW’s parallel twins with videos on YouTube and a great article in BMW Owners News.

When I got to the tech specs of the new bikes, I noticed something and thought, “Hey, I’m a pretty tech-aware guy, and if this confuses me, maybe there are other people who wonder about this as well.” I am referring to the part of the specs where BMW recommends what kind of gasoline should be used for the bike. In this instance (and you can refer back page 69 of the January issue to see what I’m talking about) the F 750 GS spec is for 91 RON gas, while the F 850 GS is rated for 95 RON fuel. The spec sheet calls 91 RON “regular” and 95 RON “premium,” but most of us reading this magazine don’t see 91 next to “regular” on the gas pumps we use.

Perhaps the confusion stems in part from not knowing that when you read the tech specs for a BMW motorcycle, BMW is referring to the sticker on the pump in Germany. The good news is that at its most basic level, regular gas is regular gas, and 91 RON in Germany is equivalent to 87 AKI in the United States. Premium is the same, and while premium gasoline is often called “super” by some retailers, 95 RON in Germany is equivalent to 91 AKI in the USA and Canada. What they call “super plus” in Germany in 98 RON, or 93 AKI stateside.

You can stop reading right there and take away a couple of things. First is the knowledge that regular means regular and premium means premium (or super), and if that’s all you remember when it comes to your motorcycle, you’re fine. The second is nobody really bothers specifying those mid-grade fuels, so in general you can just skip them unless they’re your only choice for some reason.

On U.S. and Canadian pumps, you’re generally presented with three choices: 87, 89 and 93. Some stations throw in 88, 91 or even 95. We think of gasoline as the go-juice for our motorcycles, but there’s more to it than just suck, squish, boom, blow, especially when it comes to the amazing technology built into our modern motorcycles. In the old days when one twist grip was the throttle and the other advanced the timing, the rider had to have a feel for what was going on with the bike at all times. Fuel injection and computers have taken that need from us, thankfully, but that doesn’t mean we can’t understand what’s going on.

The abbreviations we see used to describe the quality of gasoline are varied, but luckily there are only a few of them.

- RON: Research Octane Number, used in Europe and most other places in the world

- MON: Motor Octane Number, usually accompanies RON

- AKI: Anti-Knock Index, used in Brazil, Canada, the U.S. and a few other countries

- RdON: Observed Road Octane Number, not seen on pumps

The RON of a particular blend of gasoline is determined by scientists and engineers who run the gas through a test engine at 600 RPM under tightly controlled conditions. The engine itself is special, because unlike your motorcycle, the compression ratio of the engine can be altered on the fly. MON is determined at 900 RPM using fuel that’s been warmed up, and the special engines used for MON testing have variable ignition timing on them.

AKI isn’t determined by testing, but rather by mathematics. You take the RON, add the MON to it, then divide the sum by two. You may recognize the formula (R + M)/2 as what we commonly refer to as an average, and you’d be right. Where MON is usually 8 to 12 numbers below RON, AKI is usually 4 to 6 numbers below RON, right about in the middle between MON and RON.

The K in AKI stands for Knock, and you don’t want your engine to knock. When an engine knocks, that means the air-fuel mixture in the cylinders is burning unevenly or incompletely, neither of which is good for your engine. While there are other things that can cause knocking, such as worn-out spark plugs or excessive carbon deposits in the cylinders, we’re talking about octane here, so that’s what we’re going to focus on. (Maintenance note: if two or three tanks of the proper AKI-rated gasoline don’t eliminate your engine knocking problems, put in new spark plugs.)

Here’s the important part: gasoline with a higher AKI (or RON or MON) can withstand more compression at a given temperature before it ignites. High-performance engines with high compression require high AKI gasoline, it’s that simple. You might save a little money by putting 87 in your engine that requires 91, but over time you’re not doing yourself any favors by introducing increased wear and poorer performance to your motorcycle engine.

At the gas station closest to my house (at the time of this writing (mid-December 2018), 87 AKI gas costs $1.99 per gallon and 93 AKI costs $2.89 per gallon, a difference of 90 cents a gallon. My 2005 R 1200 GS holds 5.3 gallons of fuel, so filling a completely dry tank would cost me $10.55 with 87 and $15.32 with 93. Filling my tank with 93 therefore costs me $4.77 over filling it with 87.

The compression ratio of my engine is 11.0:1, and BMW specifies the use of 95 RON gasoline – 91 AKI. Since my nearest gas station doesn’t sell 91, it’s better to go over (93) than under (89). Having said that, one of the great things about the GS platform is that BMW intends them to be ridden anywhere at any time, and incorporates whiz-bang computer programming called Automatic Knock Control to enable cheapskates all over the world to use 91 RON (87 AKI) gasoline.

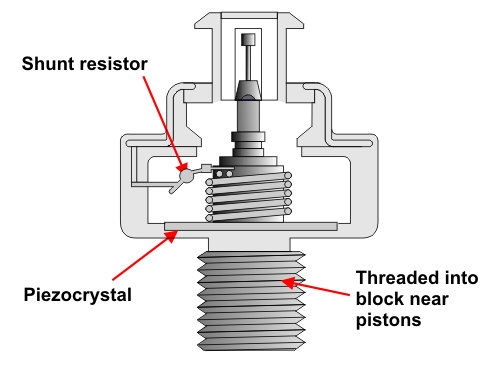

Automatic knock control is typical for automotive engine management systems, and it’s becoming increasingly pervasive in motorcycles. Its function is simple: when the sensors detect knocking, the bike’s computers delay the introduction of the spark into the cylinder. This gives the piston an extra split second to compress the fuel-air mixture to the correct level. Due to the process of four-stroke internal combustion, this means that the piston is likely on its downstroke when the knock-retarded ignition takes place. This robs you, the rider, of power and decreases fuel efficiency over time.

One of the problems with engine knock is that by the time you actually hear it, the damage is done. Engine knock sounds occur around 6-8 kHz, which is in the middle of humans’ hearing range, but they’re not typically loud sounds until you really have a problem. You’re more likely to feel knocking through your butt, hands and feet before you hear it. Once it gets bad enough to be audible, you could be looking at serious engine problems.

The way to prevent knock, then, is to use fuel with an appropriate octane rating for the compression ratio of the cylinders. This comes down to math yet again, but it’s easy math if you have the data. Find out the volume of the cylinder with the piston at bottom dead center and compare that to the volume of the cylinder with the piston at top dead center; the resulting ratio represents what kind of gas you need to run in your bike for peak performance. An engine with a high compression ratio, as is the case with the above-mentioned F 850 GS, requires higher octane gasoline than an engine with a low compression ratio.

Determining the volume is a little more complicated, math-wise. You have to know the bore and stroke of the cylinder, the compression height of the piston as well as its dome height (or dish depth), the piston-to-deck clearance (bore squared x 0.7854 x distance between piston and deck at TDC), and even the thickness and bore of the head gasket. Then and only then can you run the formula through to determine the compression ratio. This is perhaps why we take the manufacturer’s word for it when it comes to compression ratios.

Here’s where the monkey gets the wrench, though. Because of any number of myths and a certain level of ignorance as to how gasoline and internal combustion engines function, many riders believe that putting premium gas into an engine with a low compression ratio will boost performance. It simply will not. Premium gas is not better gas than regular gas, it simply has higher octane to be suited for engines with a high compression ratio. As far as your low-compression-ratio-engine is concerned, the excess octane beyond what it requires is wasted, which means the extra 30 cents a gallon you spent on that 93-octane fuel when your bike only needs 87 became dust in the wind. Unless, of course, your engine is pinging and knocking. In that case, try buying a couple of tanks of gas one octane rating higher than usual and see if that takes care of the noise. If it does, it’s time for a tune-up, because something is out of spec with your engine. If going up one grade of gasoline doesn’t work (or isn’t possible), you may need to consult a qualified motorcycle mechanic.

In the end, Super and Premium are words used by marketing experts to trick you into buying gas you think is better for your car or motorcycle rather than Regular or Mid-Grade. After all, you’re special, so your motorcycle must be special too, right? Problem is, unless you’ve got an absolute ton of money, your bike isn’t special. Certainly your 2007 R 1200 RT isn’t special, and there isn’t a gallon of 98 octane fuel anywhere in the world that’s going to improve the performance curve of your bike.

Read Part Two of this series on fuel and fueling at C2H2OH: Ethanol.